Strong tea and good books

“You can never get a cup of tea large enough or a book long enough to suit me.”

Manhattan in Reverse

I particularly enjoyed 'Watching Trees Grow' and the two Paula Myo short stories. A very good collection of short stories. The Paula Myo stories appear to take place in between the Commonwealth Saga and the Void Trilogy. Mr Hamilton, please write more stories in this universe you've created!

I particularly enjoyed 'Watching Trees Grow' and the two Paula Myo short stories. A very good collection of short stories. The Paula Myo stories appear to take place in between the Commonwealth Saga and the Void Trilogy. Mr Hamilton, please write more stories in this universe you've created!

LIFE IN THE CAT' LANE.

A fun little tale of life from the point of view of a Tuxedo Tom called Sooty in diary form. His life is thrown upside down by the arrival of an unusually behaved breed of dog, a Chow, that changes the dynamic of his home which he previously ruled without question.

A fun little tale of life from the point of view of a Tuxedo Tom called Sooty in diary form. His life is thrown upside down by the arrival of an unusually behaved breed of dog, a Chow, that changes the dynamic of his home which he previously ruled without question.Light-hearted, not so serious, and fairly interesting, it was a decent read and seeing as sales of it go to charity, it is for a good cause as well.

The Garden of Burning Sand

***I recieved this book for free under the Goodreads First Reads giveaway scheme in exchange for an honest review.***

When I found I'd won my first book under the giveaway scheme after entering dozens I was excited but this was slightly dissipated when I read what book I had won. Then when it arrived a few weeks later and it was a hefty hard-cover I thought, how am I going to lug that in my briefcase to and from work on the train?

I put it off for three maybe four books but I shouldn't have. I was wrong to be disappointed. It is a very good story that carefully, skilfully, and compassionately explores the issues affecting women and girls in sub-Saharan Africa, and how the decisions we make as relatively rich westerners, who have access to healthcare, a relatively corruption free justice system (some police officers aside) and education, affect those who have none of these things and a lot less beside.

The story follows a rich young American female, the archetypical 'sploilt brat with a trust fund' trying to do good in the world and help those less fortunate than herself. Except that she doesn't come across as spoilt, or a brat.

The exposition of the justice system in Zambia, the difficulty to achieve convictions, the superstitions that surround medical science as practiced in the west, and the horrors that AIDS and HIV has on societies in Africa are eye-opening, evocative, and effective.

The main character is developed well, others not so much, it is a first person book written in the third. I enjoyed it, it was interesting and informative. The story was good with a great deal of suspense, mystery, and twists that did mean the ending was not a foregone conclusion.

I heartily recommend it and will probably be purchasing Mr Addison's first novel, A Walk Across the Sun to see if it is just as good, or better.

Foundation and Empire

Top notch science fiction that despite being over sixty years old is still gripping, fresh, and relevant. The series has not aged and is a great achievement.

Top notch science fiction that despite being over sixty years old is still gripping, fresh, and relevant. The series has not aged and is a great achievement.

The Lost Stars - Perilous Shield (book 2) (Lost Stars 2)

Very slow start, that got better as it went on. The 'inside the head' moments of Drakon and Iceni were excruciating to read.

Very slow start, that got better as it went on. The 'inside the head' moments of Drakon and Iceni were excruciating to read.

Inverted World (S.F. Masterworks)

Fantabidosy. The twist at the end threw me as I didn't expect it, I found the novel and the concept interesting and clever. This is the second novel I've enjoyed by this author, will hunt down some more.

Fantabidosy. The twist at the end threw me as I didn't expect it, I found the novel and the concept interesting and clever. This is the second novel I've enjoyed by this author, will hunt down some more.

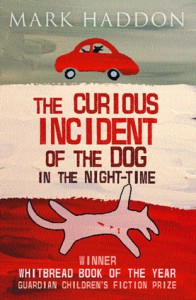

A Curiously interesting and excellent book

It is 9 minutes past six in the evening. I am writing a review of a murder mystery novel. I like murder mystery novels as they involve puzzles where you try to solve the mystery before the answer is revealed.

The novel I am reviewing is written by a boy with Asperger's Syndrome. I like reviews because you always know what someone thought of the book they are reviewing by the number of stars they have given the novel at the top of their review.

It is a social convention that books are marked out of five, and that the more stars you give them, the more you liked the book.

(A convention is a set of agreed, stipulated, or generally accepted standards)

I liked this book a lot. That is why I gave it five stars. What first drew me to this book was the title. The title is very long which is unusual for a novel. The title of this book is 'The Curious Incident of the Dog In The Night-Time' and it says the author is Mark Haddon.

But it isn't.

I have read the book and the author is actually Christopher Boone, this is one of the mysteries contained within it. In the book he states throughout that he is writing this book because he likes murder mystery novels as well, and he had a mystery he needed to solve. (He later had two mysteries to solve).

The initial mystery he had to solve was about a dog that had been killed with a garden fork which he found at 7 minutes past midnight. The dog belonged to his neighbour, this neighbour was a friend of his. The neigbour came out after a while and accused Christopher of killing the dog. As did the police officer, who touched Christopher. So Christopher hit him.

I think that day must have been a Black Day for Christopher due to what happened, if he had been on the bus I think he would have seen four yellow cars in a row. When I read this book however I saw 5 red cars in a row and so it was a Super Good Day and I enjoyed the book very much, I also had a strawberry milkshake on the way home which was good.

Christopher then sets out to solve the mystery of who killed the dog with the garden fork and proceeds to investigate this crime, against his father's wishes. This is the main premise of the book at the start before it develops into a wider story arc.

I'd like to tell you more about the book but my friend says that doing so would make my review full of spoilers (this would diminish or destroy the value of the book to those who have not read it), so I won't do that.

Instead I will finish my review here. And then I will get the train home. And then I will read another book and write another review. And I know I can do this because Christopher Boone has taught me that I can do anything.

The Curious Incident of the Dog in the Night-Time

It is 9 minutes past six in the evening. I am writing a review of a murder mystery novel. I like murder mystery novels as they involve puzzles where you try to solve the mystery before the answer is revealed.

It is 9 minutes past six in the evening. I am writing a review of a murder mystery novel. I like murder mystery novels as they involve puzzles where you try to solve the mystery before the answer is revealed.The novel I am reviewing is written by a boy with Asperger's Syndrome. I like reviews because you always know what someone thought of the book they are reviewing by the number of stars they have given the novel at the top of their review.

It is a social convention that books are marked out of five, and that the more stars you give them, the more you liked the book.

(A convention is a set of agreed, stipulated, or generally accepted standards)

I liked this book a lot. That is why I gave it five stars. What first drew me to this book was the title. The title is very long which is unusual for a novel. The title of this book is 'The Curious Incident of the Dog In The Night-Time' and it says the author is Mark Haddon.

But it isn't.

I have read the book and the author is actually Christopher Boone, this is one of the mysteries contained within it. In the book he states throughout that he is writing this book because he likes murder mystery novels as well, and he had a mystery he needed to solve. (He later had two mysteries to solve).

The initial mystery he had to solve was about a dog that had been killed with a garden fork which he found at 7 minutes past midnight. The dog belonged to his neighbour, this neighbour was a friend of his. The neigbour came out after a while and accused Christopher of killing the dog. As did the police officer, who touched Christopher. So Christopher hit him.

I think that day must have been a Black Day for Christopher due to what happened, if he had been on the bus I think he would have seen four yellow cars in a row. When I read this book however I saw 5 red cars in a row and so it was a Super Good Day and I enjoyed the book very much, I also had a strawberry milkshake on the way home which was good.

Christopher then sets out to solve the mystery of who killed the dog with the garden fork and proceeds to investigate this crime, against his father's wishes. This is the main premise of the book at the start before it develops into a wider story arc.

I'd like to tell you more about the book but my friend says that doing so would make my review full of spoilers (this would diminish or destroy the value of the book to those who have not read it), so I won't do that.

Instead I will finish my review here. And then I will get the train home. And then I will read another book and write another review. And I know I can do this because Christopher Boone has taught me that I can do anything.

A War of Gifts: An Ender Story

So... very short even for a novella. The back cover wants $6 for it. If I paid the £ equivalent I was ripped off. Not much to the story really and the length didn't allow anything remotely fascinating to occur. Quite a disappointment

So... very short even for a novella. The back cover wants $6 for it. If I paid the £ equivalent I was ripped off. Not much to the story really and the length didn't allow anything remotely fascinating to occur. Quite a disappointment

Evolutionary Void

A fantastic conclusion to what is an epic series, the combination of science fiction, fantasy, political intrigue, and a mystery just makes the entire series as good as the original Commonwealth Saga (Pandora's Star / Judas Unchained). Although this book had slow bits in my opinion (The Edeard storyline wasn't as strong at first with all the backtracking but the end was a satisfying conclusion.

A fantastic conclusion to what is an epic series, the combination of science fiction, fantasy, political intrigue, and a mystery just makes the entire series as good as the original Commonwealth Saga (Pandora's Star / Judas Unchained). Although this book had slow bits in my opinion (The Edeard storyline wasn't as strong at first with all the backtracking but the end was a satisfying conclusion.

The Temporal Void: The Void trilogy: Book Two (Void Trilogy 2)

Excellent and gripping. The blend of science fiction and fantasy is expertly done and I actually enjoyed the fantasy story so much more than the science fiction.

Excellent and gripping. The blend of science fiction and fantasy is expertly done and I actually enjoyed the fantasy story so much more than the science fiction.

Marching to the Fault Line

An interesting book that examines the intrigue, machinations, and back channel meetings that took place during the miners’ strike and which seeks to underscore and examine why it failed through the use of documents obtained under Freedom of Information and through interviews with the key players on either side.

The book takes an issue that is black and white for many depending on your politics (NUM good, Thatcher evil) or (Thatcher good, NUM evil) and demonstrates that it is really many shades of grey, depressing grey. The authors reveal that throughout the strike and right through until January 1985 that the Government were not sure they were going to ‘win’ the dispute with the NUM, and they also reveal that throughout the dispute there were many attempts at negotiating a deal between the National Coal Board (NCB), and the National Union of Mineworkers (NUM).

Talks were orchestrated by Stan Orme, the Labour Shadow Secretary of Energy between Scargill and McGregor. Separate talks were arranged by Bill Keys, a left wing printworkers union leader between Lord Whitelaw (Deputy Prime Minister) and Mick McGahey, the Communist vice president of the National Union of Mineworkers. Talks were held by Norman Willis, General Secretary of the TUC (Trade Unions Congress) and Iain McGregor (Chairman of the NCB).

All of these talks, with the exception of the Scargill one, produced some form of agreement. An agreement that the union leaders involved at each point felt was reasonable, was something that would save the NUM, and was something that would be a negotiated settlement of the dispute that would allow the NUM to remain strong. Each time any agreement was rejected by Scargill according to the authors.

Scargill’s finances are put to the sword as well and his unusual financial arrangements come under the spotlight and are questioned by the authors. Also examined are his justifications for sending Roger Windsor to Libya for money, and the fact that after the strike Scargill apparently told the other Union leaders who had tried to help (even though he publicly accused them repeatedly of doing nothing and being class traitors) that the NUM could not repay the many hundreds of thousands of pounds that many other trade unions had lent to the NUM to help them in their struggle.

The sore conclusion from this book, disputed by those on the left and Seamus Milne, is that it was Scargill’s intransigence, his refusal to compromise, or accept a 95% victory that led to the Mineworkers losing the strike and going back to work without a settlement and without having prevented what eventually happened to miners throughout Britain.

What is also clear is that the Government were heavily involved and that Peter Walker, who could have been in Brighton but for the strike, played a crucial role in ensuring that it was the Government that endured, rather than those on strike.

It is also clear, through the facts presented, that this was not just a dispute between the NUM and the NCB, or between Scargill and Thatcher, but in fact a civil war within the mining community, miner versus miner. Many thousands of miners, especially in Nottinghamshire refused to strike and wanted to work, it was here that clashes occurred between miner and miner, between pickets and police. Where violent intimidation of ‘scabs’, those who wanted to work, occurred and how the strike organised was not as effective as in the past due to poor organisation, police tactics, and a lack of unity amongst the miners.

From this book the conclusion drawn is that Kinnock tried hard to help and was a noble man in the eyes of the authors, that McGahey knew a compromise had to be sought but could not challenge Scargill, that Bill Keys tried his best to negotiate a settlement, and that the TUC were marginalised by Scargill and told to stay out of it but still tried to prevent the complete and utter defeat that the miners eventually suffered. Scargill on the other hand is vilified and on the evidence presented, rightly viewed as a fool who was on a ideological class war for which only total victory would do and for which any deal with the Government/NCB was not enough unless they capitulated.

As for Scargill who refused to co-operate with the authors, in 1984 he went into a strike with a big union and a small house. When he retired as President of the National Union of Minerworkers in 2002 he was the head of a small union, and had a big house. He also receives an extravagent pension while setting himself up for a job working for a NUM fund as well as claiming to retain the use of a 3 bedroom flat paid for by the NUM in the Barbican. According to the authors of this history of the strike, "the miners trusted Arthur Scargill with their homes, their families, their future, their safety, everything they had and he let them down". For Scargill the only history he wants written is one which proves he was right.

Marching to the Fault Line

An interesting book that examines the intrigue, machinations, and back channel meetings that took place during the miners’ strike and which seeks to underscore and examine why it failed through the use of documents obtained under Freedom of Information and through interviews with the key players on either side.

An interesting book that examines the intrigue, machinations, and back channel meetings that took place during the miners’ strike and which seeks to underscore and examine why it failed through the use of documents obtained under Freedom of Information and through interviews with the key players on either side.The book takes an issue that is black and white for many depending on your politics (NUM good, Thatcher evil) or (Thatcher good, NUM evil) and demonstrates that it is really many shades of grey, depressing grey. The authors reveal that throughout the strike and right through until January 1985 that the Government were not sure they were going to ‘win’ the dispute with the NUM, and they also reveal that throughout the dispute there were many attempts at negotiating a deal between the National Coal Board (NCB), and the National Union of Mineworkers (NUM).

Talks were orchestrated by Stan Orme, the Labour Shadow Secretary of Energy between Scargill and McGregor. Separate talks were arranged by Bill Keys, a left wing printworkers union leader between Lord Whitelaw (Deputy Prime Minister) and Mick McGahey, the Communist vice president of the National Union of Mineworkers. Talks were held by Norman Willis, General Secretary of the TUC (Trade Unions Congress) and Iain McGregor (Chairman of the NCB).

All of these talks, with the exception of the Scargill one, produced some form of agreement. An agreement that the union leaders involved at each point felt was reasonable, was something that would save the NUM, and was something that would be a negotiated settlement of the dispute that would allow the NUM to remain strong. Each time any agreement was rejected by Scargill according to the authors.

Scargill’s finances are put to the sword as well and his unusual financial arrangements come under the spotlight and are questioned by the authors. Also examined are his justifications for sending Roger Windsor to Libya for money, and the fact that after the strike Scargill apparently told the other Union leaders who had tried to help (even though he publicly accused them repeatedly of doing nothing and being class traitors) that the NUM could not repay the many hundreds of thousands of pounds that many other trade unions had lent to the NUM to help them in their struggle.

The sore conclusion from this book, disputed by those on the left and Seamus Milne, is that it was Scargill’s intransigence, his refusal to compromise, or accept a 95% victory that led to the Mineworkers losing the strike and going back to work without a settlement and without having prevented what eventually happened to miners throughout Britain.

What is also clear is that the Government were heavily involved and that Peter Walker, who could have been in Brighton but for the strike, played a crucial role in ensuring that it was the Government that endured, rather than those on strike.

It is also clear, through the facts presented, that this was not just a dispute between the NUM and the NCB, or between Scargill and Thatcher, but in fact a civil war within the mining community, miner versus miner. Many thousands of miners, especially in Nottinghamshire refused to strike and wanted to work, it was here that clashes occurred between miner and miner, between pickets and police. Where violent intimidation of ‘scabs’, those who wanted to work, occurred and how the strike organised was not as effective as in the past due to poor organisation, police tactics, and a lack of unity amongst the miners.

From this book the conclusion drawn is that Kinnock tried hard to help and was a noble man in the eyes of the authors, that McGahey knew a compromise had to be sought but could not challenge Scargill, that Bill Keys tried his best to negotiate a settlement, and that the TUC were marginalised by Scargill and told to stay out of it but still tried to prevent the complete and utter defeat that the miners eventually suffered. Scargill on the other hand is vilified and on the evidence presented, rightly viewed as a fool who was on a ideological class war for which only total victory would do and for which any deal with the Government/NCB was not enough unless they capitulated.

As for Scargill who refused to co-operate with the authors, in 1984 he went into a strike with a big union and a small house. When he retired as President of the National Union of Minerworkers in 2002 he was the head of a small union, and had a big house. He also receives an extravagent pension while setting himself up for a job working for a NUM fund as well as claiming to retain the use of a 3 bedroom flat paid for by the NUM in the Barbican. According to the authors of this history of the strike, "the miners trusted Arthur Scargill with their homes, their families, their future, their safety, everything they had and he let them down". For Scargill the only history he wants written is one which proves he was right.

The Book Thief (Definitions)

A good story, narrated by death, about a girl in Germany, during World War 2, and her trials and tribulations in dealing with life in a small German town.

A good story, narrated by death, about a girl in Germany, during World War 2, and her trials and tribulations in dealing with life in a small German town.

1

1